One of the largest rotating structures ever found in the universe – likened to a teacups ride at a theme park – has been spotted some 140 million light-years from Earth.

The giant spinning cosmic filament, which has a "razor-thin" string of galaxies embedded within it, was identified by an international team led by the University of Oxford.

Their findings, published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, could offer valuable new insights into how galaxies formed in the early universe.

Cosmic filaments are the largest known structures in the universe: vast, thread-like formations of galaxies and dark matter that form a cosmic scaffolding. They also act as 'highways' along which matter and momentum flow into galaxies.

Nearby filaments containing many galaxies spinning in the same direction – and where the whole structure appears to be rotating – are ideal systems to explore how galaxies gained the spin and gas they have today. They can also provide a way to test theories about how cosmic rotation builds up over tens of millions of light-years.

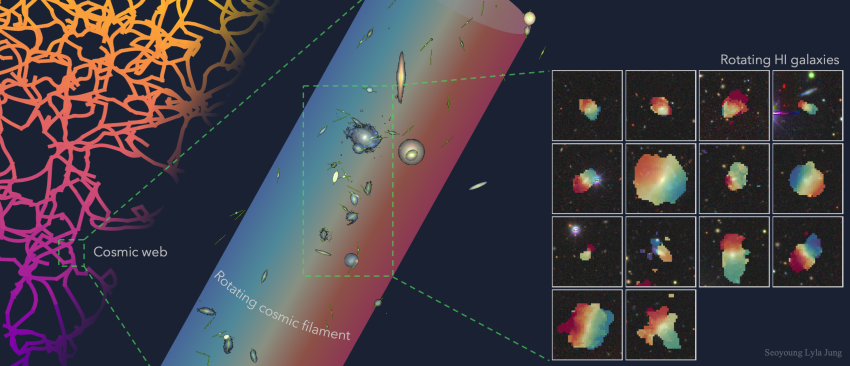

In the new study, researchers found 14 nearby galaxies rich in hydrogen gas, arranged in a thin, stretched-out line about 5.5 million light-years long and 117,000 light-years wide. This structure sits inside a much larger cosmic filament roughly 50 million light-years long, which contains more than 280 other galaxies.

Remarkably, many of these galaxies appear to be spinning in the same direction as the filament itself – far more than if the pattern of galaxy spins was random.

This challenges current models and suggests that cosmic structures may influence galaxy rotation more strongly or for longer than previously thought.

The researchers found that the galaxies on either side of the filament's spine are moving in opposite directions, suggesting that the entire structure is rotating. Using models of filament dynamics, they inferred the rotation velocity of 110 km/s and estimated the radius of the filament's dense central region at approximately 50 kiloparsecs (about 163,000 light-years).

Co-lead author Dr Lyla Jung, of the University of Oxford, said: "What makes this structure exceptional is not just its size, but the combination of spin alignment and rotational motion.

"You can liken it to the teacups ride at a theme park. Each galaxy is like a spinning teacup, but the whole platform – the cosmic filament – is rotating too. This dual motion gives us rare insight into how galaxies gain their spin from the larger structures they live in."

The filament appears to be a young, relatively undisturbed structure. Its large number of gas-rich galaxies and low internal motion – a so-called "dynamically cold" state – suggest it's still in an early stage of development.

Since hydrogen is the raw material for star formation, galaxies that contain much hydrogen gas are actively gathering or retaining fuel to form stars. Studying these galaxies can therefore give a window into early or ongoing stages of galaxy evolution.

Hydrogen-rich galaxies are also excellent tracers of gas flow along cosmic filaments. Because atomic hydrogen is more easily disturbed by motion, its presence helps reveal how gas is funnelled through filaments into galaxies – offering clues about how angular momentum flows through the cosmic web to influence galaxy morphology, spin, and star formation.

The discovery could also inform future efforts to model intrinsic alignments of galaxies, a potential contaminant in upcoming weak lensing cosmology surveys with European Space Agency's Euclid mission and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile.

Co-lead author Dr Madalina Tudorache, of the University of Oxford, added: "This filament is a fossil record of cosmic flows. It helps us piece together how galaxies acquire their spin and grow over time."

The international team used data from South Africa's MeerKAT radio telescope, one of the world's most powerful telescopes, comprising an array of 64 interlinked satellite dishes.

This spinning filament was discovered using a deep survey of the sky called MIGHTEE, which is led by Professor of Astrophysics Matt Jarvis, of the University of Oxford. This was combined with optical observations from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) and Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) to reveal a cosmic filament exhibiting both coherent galaxy spin alignment and bulk rotation.

Professor Jarvis said: "This really demonstrates the power of combining data from different observatories to obtain greater insights into how large structures and galaxies form in the universe."

The study also involved researchers from the University of Cambridge, University of the Western Cape, Rhodes University, South African Radio Astronomy Observatory, University of Hertfordshire, University of Bristol, University of Edinburgh, and the University of Cape Town.

ENDS

Media contacts

Sam Tonkin

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877 700

Dr Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877 699

Science contacts

Dr Madalina N. Tudorache

University of Cambridge/Oxford

madalina.tudorache@ast.cam.ac.uk

Dr Lyla S. Jung

University of Oxford

Professor Matt Jarvis

University of Oxford/University of the Western Cape

Images & captions

Caption: A figure illustrating the rotation of neutral hydrogen (right) in galaxies residing in an extended filament (middle), where the galaxies exhibit a coherent bulk rotational motion tracing the large-scale cosmic web (left).

Credit: Lyla Jung

Further information

The paper 'A 15 Mpc rotating galaxy filament at redshift z = 0.032' by Madalina N. Tudorache, Lyla S. Jung and Matt Jarvis et al. has been published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/staf2005.

Notes for editors

About the University of Oxford

Oxford University has been placed number 1 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for the tenth year running, and number 3 in the QS World Rankings 2024. At the heart of this success are the twin-pillars of our ground-breaking research and innovation and our distinctive educational offer.

Oxford is world-famous for research and teaching excellence and home to some of the most talented people from across the globe. Our work helps the lives of millions, solving real-world problems through a huge network of partnerships and collaborations. The breadth and interdisciplinary nature of our research alongside our personalised approach to teaching sparks imaginative and inventive insights and solutions.

Through its research commercialisation arm, Oxford University Innovation, Oxford is the highest university patent filer in the UK and is ranked first in the UK for university spinouts, having created more than 300 new companies since 1988. Over a third of these companies have been created in the past five years. The university is a catalyst for prosperity in Oxfordshire and the United Kingdom, contributing around £16.9 billion to the UK economy in 2021/22, and supports more than 90,400 full time jobs.

About the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science.

The RAS organises scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognises outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

The RAS accepts papers for its journals based on the principle of peer review, in which fellow experts on the editorial boards accept the paper as worth considering. The Society issues press releases based on a similar principle, but the organisations and scientists concerned have overall responsibility for their content.

Keep up with the RAS on Instagram, Bluesky, LinkedIn, Facebook and YouTube.